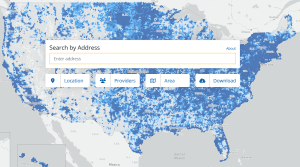

From all over the country, I’m hearing stories about ISPs who are gaming the FCC broadband maps in order to block area from being eligible for the BEAD grants. It’s relatively easy for an ISP to do this. All that’s needed is to declare the capability to deliver a speed of 100/20 Mbps in the FCC maps.

From all over the country, I’m hearing stories about ISPs who are gaming the FCC broadband maps in order to block area from being eligible for the BEAD grants. It’s relatively easy for an ISP to do this. All that’s needed is to declare the capability to deliver a speed of 100/20 Mbps in the FCC maps.

ISPs can largely do this with impunity since there is nothing wrong with them doing this. The archaic FCC rules allow ISPs to claim ‘up-to’ marketing speeds in the maps, and ISPs can self-determine the speed they want to declare.

A lot of ISPs decided to start claiming 100/20 Mbps capabilities in the last update to the FCC maps. This is being done across technologies. We’ve suddenly found rural DSL claimed at speeds of 100/20 Mbps and faster. Older DOCSIS 3.0 cable networks that previously declared upload speeds of 8 or 10 Mbps are suddenly in the FCC maps with 20 Mbps upload speeds. Some WISPs and FWA cellular carriers are claiming speeds of 100/20 Mbps across a large geographic footprint that doesn’t match the capabilities from its tower locations.

It’s not hard to understand the motivation for this. We’ve seen this before. Just before the FCC was to announce the eligible areas for the RDOF reverse auction, CenturyLink and Frontier declared that tens of thousands of Census blocks suddenly had the capability to deliver speeds of 25/3 Mbps. This was the speed in the FCC maps that would have made these areas ineligible for the RDOF auction. The FCC rightfully rejected these last-minute claims. But if the telcos had been less greedy and had declared a smaller number of Census blocks, they may well have gotten away with the deception. The motivation of these telcos was obvious – they didn’t want anybody else funded to bring broadband to their monopoly service territories, even though they were not delivering decent broadband.

The motivation to do this today is identical. When an ISP declares 100/20 Mbps speed capability, the area is removed from BEAD grant eligibility. The ISP operating in that area will have squelched a new competitor from entering the market using BEAD grants.

The ISPs aren’t finished with this effort. I know several communities where the cable company recently knocked on the door at City Hall to say they are going to upgrade the cable networks this year. These communities are expecting that the cable companies will try to kill BEAD eligibility by declaring the upgrades in the upcoming BEAD map challenges being done in each state.

The NTIA’s and the FCC’s response to this issue is that it is the responsibility of communities to police this issue and to engage in the upcoming state BEAD mapping challenges. I can barely talk about that position without sputtering in anger. Most counties are not equipped to understand the real speeds that are available from an ISP. From my own informal survey, I don’t think that even 10% of counties are considering a map challenge.

But even communities willing to tackle a map challenge will find an incredibly difficult time. First, many states only have a 30-day long map challenge process, and some of the challenges are already underway, with many more challenges to start very soon. Communities have to somehow convince customers of the suspect ISPs to take a speed test multiple times a day in a specific manner. That is hard to do under any circumstances, but particularly hard to do considering the short time frame and specificity of the challenge process.

Consider a real-life example of the difficulty of doing this. I know a county where a WISP claims 100/20 Mbps speed for over five hundred homes in a corner of the county. The county purchased trailing 12-months of Ookla speed test data, and there was only one speed test for this ISP in that area in the last year. If the State Broadband Office won’t accept that as proof for a valid challenge, the County can’t convince nonexistent customers to take a speed test.

This feels like another example of the NTIA ‘protecting the public’ by requiring a lot of proof for a map challenge. The fact is that the folks living in rural areas know the ISPS that work and don’t work. If a ISP appears with decent speeds in an area with no good broadband, word of mouth spreads quickly and a lot of people try the ISP. If a new ISP gains almost no customers, they are either making bogus claims of speed capabilities or they have prices that nobody can afford. Market success should be one of the criteria for a map challenge, and States should invalidate claims by any ISP who have only a sprinkling of customers in an area from blocking BEAD grants. Unfortunately, the FCC does not gather actual customer data in the same detail as the FCC maps – they only gather the speeds claimed by ISPs and the supposed capability to connect customers within 10 days.

The bottom line of all of this is that map manipulation is going to mean that a lot of areas will be excluded from the BEAD grants. Counties are ill-equipped to do the map challenges, and even motivated counties will have a hard time mounting a successful map challenge.

I expect my blogs in a few years will be full of stories of the neighborhoods that got left behind by BEAD and which still won’t have an ISP option with decent speeds. I’m predicting this will be millions of homes. Unfortunately, those homes will be scattered, and it will not be enough homes to drive another big grant program. I fear these folks will be left behind, served only by the ISP that exaggerated the speeds in the FCC map. In the case of the FCC maps, it seems that cheating pays.

Like this:

Like Loading...

If there is any upside to the interminable delays in the BEAD grant process, it’s that American manufacturers have had the time to gear up to build the components needed to build broadband networks in the U.S.

If there is any upside to the interminable delays in the BEAD grant process, it’s that American manufacturers have had the time to gear up to build the components needed to build broadband networks in the U.S.